How do chess players develop their skill?

There is no doubt that strengthening tactics--pattern recognition and calculation--is essential. Learning openings and endgames helps also.

Studying classic games is both enjoyable and productive. Paul Morphy's games help teach the fundamental principles of development in the opening--mobilization of forces, time, vulnerability, coordination of forces. His games also offer an abundance of tactical positions where pattern recognition and calculation skills can be honed through proper training.

Reading Bobby Fischer,

My 60 Memorable Games may drill into the reader's memory his famous line, "tactics flow from a positionally superior game," and also may set into the memory the knight sacrifice on h7 to rip open the pawn shield in front of Black's king that was the context of that remark. Another sacrificial attack that should be familiar to most chess players was played in Rotlewi -- Rubinstein 1907. It appears in many books on tactics. I have seen the critical position during tactics training both on

Chess Tempo and while using

Chess.com's Tactics Trainer. The patterns in this game inspired Vishy Anand in his brilliant miniature against Levon Aronian at the 2013 Tata Steel Chess Tournament.

As a devotee of the French Defense, I have spent many hours looking for ways to secure an advantage, or at least a playable game with imbalances, against the Exchange variation. Years ago on this blog, I declared my contempt for the Exchange variation, calling it "cowardly" (see "

French Perfume"). Even so, I have lost a handful of games over-the-board against the Exchange French and have lost far more than a few in online play. Still, I have found some success in online play, especially blitz, drawing inspiration from Victor Korchnoi's fine miniature against Stefano Tatai.

Tatai,Stefano (2455) -- Kortschnoj,Viktor (2665) [C01]

Beersheba (6), 1978

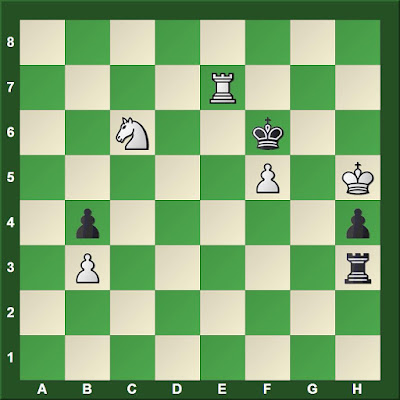

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.exd5 exd5 4.Bd3 c5 5.Nf3 Nc6 6.Qe2+ Be7 7.dxc5 Nf6 8.h3 0–0 9.0–0 Bxc5 10.c3 Re8 11.Qc2 Qd6

White to move

12.Nbd2 Qg3 13.Bf5 Re2 14.Nd4 Nxd4 0–1

Whan I have the Black side of the Exchange French, having my queen and two minor pieces arranged on c5, c6, and d6 as in the diagram above fills me with confidence, especially when White voluntarily weakens the g3 square with h2-h3 (see "

Find the Blow").

Last night in the first round of the Turkey Quads at the

Spokane Chess Club, this game was brought back into my memory.

There was a bit of irony.

I had White and played the Exchange variation via an anti-French line with 2.c4. Careful analysis of the game after it concluded, revealed that my attention to tactical opportunities for my opponent wavered. Indeed, as one might expect from the French Exchange, White was worse until a tactical error by Black. At this point, the lessons from Tatai -- Korchnoi served me well.

Stripes,James (1750) -- Griffin,David (1606) [C01]

Turkey Quads Spokane (1), 03.11.2016

1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.exd5 exd5 4.d4 c6

4...Nf6 5.Nc3 Be7, or 5...Bb4 is the usual manner of meeting this line with equality for Black.

5.Nf3

5.Nc3 Bb4 6.Nf3 is a more accurate move order, in my opinion.

5...Nf6 6.Be2

6.Nc3 is more flexible, as the bishop might go to d3 or even c4 in one move.

a) 6...Be7 7.Bd3 0–0 8.h3 dxc4 9.Bxc4 Nbd7 10.0–0

b) 6...Bd6 7.Bd3 0–0 8.0–0 dxc4 9.Bxc4 Bg4 10.h3 Bh5

6...Be7

6...Bb4+ 7.Nc3 Ne4 8.Bd2 Bxc3 9.bxc3 0–0 10.0–0 Be6 and White won in 40 moves, Vegh,E (2302)--Gonda,L (2524), Zalakaros 2013.

7.Nc3 0–0 8.0–0 dxc4

Black seizes the opportunity to give White an isolated queen pawn.

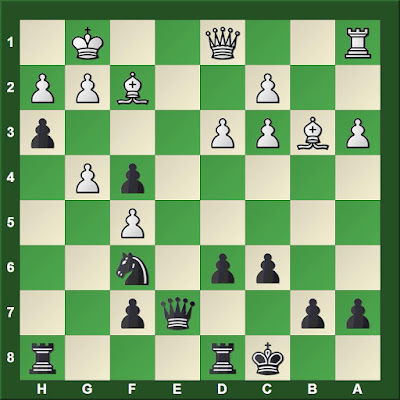

9.Bxc4 Bg4 10.Qd3?!

Black to move

10.Re1 is better, as it protects against Bxf3 and Qxd4 because Black must first protect e7.

With the move that I played, the queen can become vulnerable on this square.

Even so, I enjoyed the irony of the resemblance of my central pieces and d-pawn to Black's in Tatai -- Korchnoi 1978, but there are several aspects of the position that differ. This move was made after four minutes thought and was the first time that I moved in more than half a minute.

10...Bxf3 11.gxf3N

Here I thought for five minutes. Facing a choice between ruined pawns or being a pawn down, I opted for ruined pawns in hopes that I could find use for the g-file.

The alternative appears in a game between two players just over 2000 Elo: 11.Qxf3 Qxd4 12.Qe2 Re8 13.Bg5 Qg4 14.Qxg4 Nxg4 15.Rfe1 Kf8 and drawn after 54 moves Janiszyn,E (2007)--Chmielinska,A (2065), Zakopane 2001.

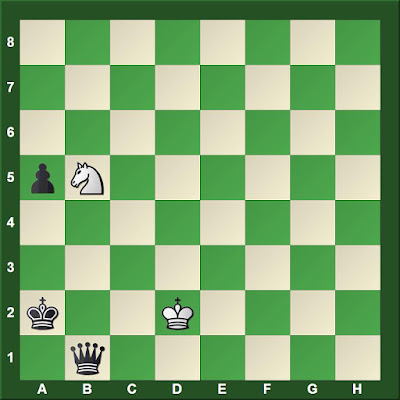

11...Nbd7 12.Kh1?

I am thinking about my long-term tactical hopes, but have not considered the tactical resources offered to my opponent.

12.a3 was something that I judged too slow because I was oblivious to Black's tactical opportunity. However, it removes Black's tactical opportunity.

Black to move

12...Re8

12...b5! alerts White to the errors of his plan, although neither player seems aware 13.Bb3 Nc5 14.Qd1 Nxb3 15.axb3 and White's pawns can hardly be worse.

12...Nb6 was a move that I thought I was prepared to meet 13.Bb3 Nfd5 14.Rg1 Re8 15.Bh6 Bf8.

13.Be3

I played a waiting move. I wanted to play Rg1, but thought that it might matter whether Black plays Bf8 or Nf8

13...Nf8

13...b5 remains possible 14.Bb3 Nc5 15.Qf5 Nxb3 16.axb3 and Black has good prospects to win.

14.Rad1

I was pleased with myself with this move because it prepares d4-d5, something that I wanted Black to think about.

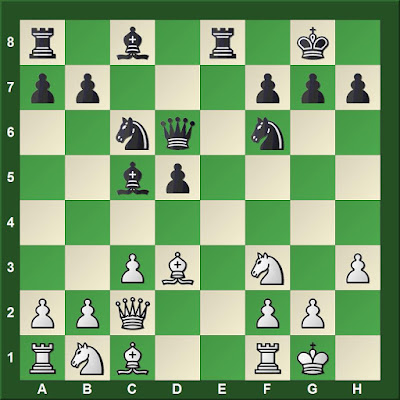

14...Qc7 15.Rg1= Ng6?

15...b5 16.Bb3

15...Rad8 would seem to be the point of Qc7, but it permits a forcing line that might give White a slight edge. 16.Bh6 Ng6 17.Rxg6 hxg6 18.Qxg6 Bf8 19.Bxg7 Bxg7 20.Rg1 Nh5 21.Qxh5 Qf4.

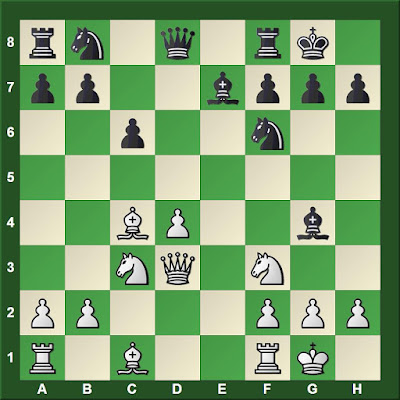

White to move

16.Rxg6!

I had been hoping for this opportunity when I played 10.Qd3 and 11gxf3.

Now that it was here, I tried to see to the end before playing this move, spending twelve minutes analyzing. The remaining annotations and all the moves of the game follow my calculations during those twelve minutes, except where noted.

I considered 16.Bh6 gxh6 17.Rxg6+ hxg6 18.Qxg6+ Kh8 19.Qxh6+ and I have had similar positions with colors reversed and found little success.

16...hxg6 17.Qxg6 Bf8

17...Rf8 18.Bh6 Ne8 and things were blurry in my imagination, but it felt comfortable. 18...Nh5 19.Rg1 was my plan ( I did not foresee 19.Bxg7! Nxg7 20.Rg1+-).

17...Bd6 18.Rg1.

18.Rg1 Rxe3

I expected 18...Nd5 19.Nxd5 cxd5 20.Bxd5 and I thought White's game was comfortable as Black's problems remain.

19.fxe3 Rd8?

A bad move in a difficult position.

a) 19...Nd5 seemed necessary to me, when 20.Nxd5 seems to offer a clear advantage (I did not consider 20.Qh5), and then 20...cxd5 (20...fxg6 21.Nxc7+ is clearly better for White) 21.Bxd5 when I still have threats and have recovered the sacrificed material with interest. In addition, my sorry pawns are substantially improved.

b) 19...Ne8 was also possible when I planned 20.Ne4 with the idea Ng5 and Qh7#.

c) 19...b5 20.Bb3 Qe7 (20...Nd5 is similar to lines above 21.Nxd5 Qd6 22.Nf6+ Qxf6 23.Qxf6 b4 24.Bxf7+ Kh8 25.Qh4#).

20.Qxf6 1–0

David resigned. He is the tournament director of this event, which includes sixteen players in four quads. We are in Quad B.